Sign up here to subscribe to the Grower2grower Ezine. Every two weeks you will receive new articles, specific to the protected cropping industry, informing you of industry news and events straight to your inbox.

Jul 2022

Year-Round Asparagus Production

By Dr Mike Nichols

Asparagus in temperate climates is the first of the “new” season vegetables. The harbinger of spring! Yields in temperate countries of mature plantings tend to be between 5-10 t/ha. In New Zealand, the harvest season for asparagus runs from early September until mid- December, after which new spears are allowed to grow into fern to produce the carbohydrates which will be stored in the swollen root system to produce the next season’s crop. In tropical countries—where there is no winter dormancy, asparagus can be harvested year-round using a method called “mother fern” production, but the quality is not so good. Thus, for the rest of the year any fresh asparagus in New Zealand must be imported from tropical countries (such as Thailand) or from temperate northern hemisphere countries such as USA in their normal spring harvest season. Because asparagus spears have a high respiration rate, they have a short shelf life and must be air-freighted—an expensive operation. There is also (of course) a biosecurity risk as there is with any imported fruits or vegetables.

Several years ago, I grew some asparagus at Massey University in deep boxes filled with coir (Nichols, 2009) and found that it grew and cropped extremely well. As a result, I suggested to Alan and Dot Bissett (Wee Red Barn, Masterton) that it might be an interesting crop to try in their high Plastic Tunnel greenhouses. The results were most impressive. Crowns (purchased from Aspara Pacific), were planted into 1m wide and 1 m high beds filled with used coir from modules, which had previously grown a crop of hydroponic strawberries. It is considered too risky to grow a second crop of strawberries in the same coir, so it is normally just disposed as a mulch in the field. Using it for a second high value crop is an excellent use of a valuable material. Planting was done in the spring when dormant crowns normally become available. The rows were (normally) 30cm apart (3 rows to the bed), and the distance between the plants in the rows was also 30 cm. There were two raised beds in each 7 m wide Haygrove house. This was to provide space for a tractor to go down the house if necessary.

In the field asparagus is normally planted in rows about 1.50 m apart, with 30 cm between plants in the row. This is equivalent to about 2 plants/m2.

The greenhouse spacing is about 2.5 plants/m2 so the plant densities are very similar, but the plant arrangement was very different..

The greenhouse crop was grown hydroponically, with watering and feeding with a full hydroponic solution undertaken daily. Towards the end of May the watering was stopped; the coir dried out, and the fern died back. This was then cut back to ground level at the end of June, and removed from the house, and the house closed up tight, to allow the sun to warm it as much as possible. In early July, the irrigation was turned on to wet the coir, and the first spears appeared towards the end of the month. Harvesting was easy, as:

- it can be done in all weather,

- the spears grow 1 m above the floor of the greenhouse, so no bending down,

- they are turgid, so easy to break off at ground level—no knife required.

Note: When robotic harvesting becomes a reality for asparagus (as it surely must), then a greenhouse operation is almost certain to be much simpler than in the field.

I am advised by Allan Bissett that the yield was approx. 1kg.plant. The normal field yield of established asparagus in New Zealand is about 6 t/ha about 300g/plant, which has a wholesale price of about $ 6/kg. This does not normally occur until the 3rd season after planting. The out-of-season asparagus from the Wee Red Barn sold for about $ 20/kg. Harvesting ceased when the outdoor crop became available in quantity (mid-October)

A yield of 1kg/plant is equivalent to 22 t/ha even with only 2 x 1 m wide beds in a 7 m wide greenhouse.

Why should this level of productivity be possible, and what potential does it offer in terms of year-round production?

Plant spacing

The yield per plant increases with increasing plant density (plants/m2) due mainly to competition for light (for photosynthesis) and for nutrients and water in the root zone. By using hydroponics competition for water and nutrients is of little importance, and it appears that the upright structure of the asparagus fern gives good penetration of light through the canopy, rather like maize, onions, or grass. The reason for the wide between the row spacing in the field is to enable tractors to cultivate between the rows in the winter, and to simplify harvesting and spraying.

Hydroponics

Soil is not a perfect growing medium physically. Sandy soils (though well aerated require frequent irrigation to be highly productive, while heavier soils (such as clay) though moisture retentive, have poor aeration characteristics. It is also possible for soils to be short of critical nutrients, which are fully available in the hydroponic nutrient solution. In the field the sandy soils dry up rapidly without regular irrigation, and the fine feeding roots (as opposed to the thick storage roots) do not develop much over 30 cm deep (see photo). Coir provides both a well aerated medium plus a good buffer for both nutrients and moisture.

Shelter from the wind

Back in the 1990’s there was considerable interest in New Zealand in the potential of selecting high yielding asparagus plants and cloning them, in order to establish a whole field with the same high yielding genetics. I can recall visiting a trial at Flock House (near Bulls) to be shocked at the variation in wind damage of the different clones. An asparagus fern requires a large amount of stored carbohydrate from the root system in order to fully develop and returns little until the fern is properly developed. If the young fern is damaged by the wind, then the loss of “capital” to the plant is considerable. In the 1960’s and 1970’s the French government asparagus breeders developed some very productive varieties (Aneto, Desto, Cito, etc) which were dwarf (presumably with short internodes). They were not very suited for green asparagus, but (presumably) the high yields were due to the lack of wind damage to the fern. High tunnels (of course) reduce or even eliminate fern damage and is another possible reason for the high yields per plant.

Fern diseases

Fern diseases (such as Stemphylium) will cause a significant loss of photosynthetic capacity, and result in the use of stored carbohydrate to produce replacement fern. This can develop in New Zealand in a wet summer, particularly in the upper North Island. The plastic tunnel provides a useful rain shelter, and in addition if it becomes necessary to spray, then rain will not wash the spray off the fern.

Optimum photosynthetic potential

Normally asparagus is harvested in the field in New Zealand from September to mid-December when the spears are then allowed to grow into fern to store carbohydrate in the root system for the following season crop. Spears do not develop into photosynthesising fern until 3-4 weeks after the final harvest. For high rates of photosynthesis plants require long days with high solar radiation levels and warm temperatures, which peak in mid-December, so that potential quantity of stored carbohydrate in the root system (and therefore future yield) will be considerably higher when harvesting ceases in mid-October, rather than 2 months later and yield will be considerably higher from a high tunnel crop which has been in fern from mid-November, and essentially had 3 extra months of good photosynthetic conditions.

Year-round production.

I have only considered the production of out-of-season (early) production, but there is no reason why the system cannot be used to produce fresh asparagus any day of the year in New Zealand.

Of course, if this became common place the $20/kg that the Bissett’s obtain for their out-of-season asparagus, would no longer apply—supply and demand factors would take over.

It appears that a good supply of carbohydrate becomes available for spear production with 4 months of fern growth. Probably 3 months is as long as the crop should be harvested, and thus a system could be developed to produce asparagus for every month of the year. Of course, producing spears in the normal harvest season might not be worth-while, in which case the fern growth period could be extended.

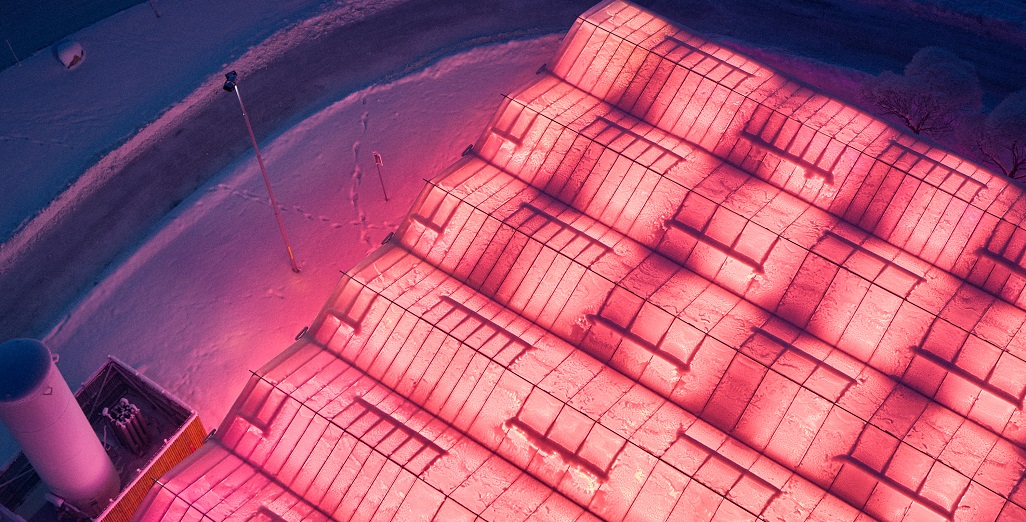

Spear production (growth) is controlled by temperature, and there may be adequate temperatures in unheated greenhouses in Northland even in the winter, but further south it may be advisable to provide some supplementary heat to the coir beds, using low voltage electric cables, or even pipes heat. Experience suggests that after the fern has been removed the beds should be topped up with coir to the original level of the beds, which tend to compact overtime.

Growing media

This information is based on the use of coir (once used for strawberry production). Coir for strawberries is essentially coir peat, with the fine particles and larger lumps removed by sieving. The question arises of should one be seeking a “chunkier” coir, to provide longer term better aeration and drainage. This would need to be imported as a distinct product, at an additional cost, as it would not be suitable for strawberries. Alternatively, however, there are considerable quantities of pine bark in New Zealand, which with hydroponics might perform to a similar level.

Sustainability

The efficient use of water and fertilizer for growing crops is going to be an increasingly important consideration for horticultural production in the future. Hydroponics offers considerable advantages over field production of asparagus in such aspects of sustainability.

By having the lower part of the bed surrounded by a waterproof material (black plastic film?) and running a drainage tube the length of the bed, then surplus irrigation water/nutrients can be recycled. This is probably not ideal, and it may be better to dump some of this solution occasionally by irrigating a grass paddock with the drainage, to avoid the possible build-up of toxins or disease in the asparagus crop.

White asparagus

The system can also be used to produce white asparagus, which has a market value of about double the price of green asparagus. This is achieved by having the benches some 20cm higher than the level of the coir in them, and then to cover them with black polythene film which is removed only when harvesting. I have only used the tetraploid variety Pacific Purple (because of its thick spears and low fibre content), but it would be interesting to see how some of the standard varieties bred for white spear production in Europe might perform.

Alternatives to tunnels

There are in New Zealand an increasing number of old (20 years +) glasshouses, essentially obsolete for producing greenhouse crops such as tomatoes, cucumbers, and sweet peppers due to the improvements in greenhouse design, such as height to the eaves, glass type and environmental control etc. This should not, however mean that they need to be demolished, as they are capable of growing very satisfactory crops of asparagus in the summer months in potato bins (see photo) filled with coir irrigated hydroponically. In the autumn they can then be dried off, the fern removed, and the bins transferred to cool stores, the coir re wetted and the cool stores heated in order to produce out-of-season white or green asparagus. The heating costs would be minimal in a cool store—which is essentially an insulated container, and although a small amount of lighting would be required (just to green up the spears) the productivity (per week) could be controlled simply by the control of temperature in the store, with higher temperatures when future demand was high, and vice versa.

Yield potential

The potential yields may be even higher as by increasing the bed width to 1.60 m, and by planting 2 more rows per bed, and establishing an additional 1.6 m bed in the 7 m wide high tunnel could result in potential yields approaching 70 t/ha, and with 3 crops possible every 2 years an annual yield of over 100 t/ha!!!!

References

Nichols, M A (2009) “Year-round asparagus production”. NZ Grower 64(10), 42-44.

Nichols, M A (2018) “The final word—Year-round asparagus production” NZ Grower, 73(6), 74-5.

Photographs

Image 1 Excellent fern growth in autumn

Image 2 White asparagus (young planting) shallow coir bed

Image 3 Spear Production Spring

Image 4 Mother fern system (Japan)

Image 5 Young plants in potato bins

To learn more contact

Dr M A Nichols

Email: oxbridge@inspire.net.nz

CLASSIFIED

Photo

Gallery

Subscribe to our E-Zine

More

From This Category

High-tech spy gear to uncover the secrets of Bumble bees in Tasmania

Cherry Production in New Zealand – Mike Nichols

Signify helps Agtira to bring locally grown cucumber to Swedish market

Dimmable Philips LED top-lighting fixtures support maximum efficiency and better use of energy

Plant & Food Research welcomes changes to gene technology regulations